Last summer Carmel Huber, director of Elephant Asia Rescue and Survival foundation, was walking home along a dark, branch-strewn path on Lamma Island, when she felt a sudden searing pain. "It was like a red hot poker had been jabbed into my ankle," she says. Her ankle began to swell, and an ugly bruise started to spread up her leg. The stick she stepped on turned out to be a baby cobra.

Encounters such as Huber's, while uncommon, happen more frequently than most people imagine. According to the Hospital Authority, public hospitals treated 67 snakebite cases in 2013, including three involving cobras.

The typical public reaction to statistics like these is fear, but they also point to a rare conservation success for Hong Kong. According to Dr Michael Lau, the city's leading snake expert, and senior programme head for biodiversity at the World Wildlife Fund in Hong Kong, the city is "very lucky" when it comes to these reptiles.

It is home to 57 indigenous snake species and two species believed to be introduced from elsewhere. With rare exceptions, land snake populations here are thriving.

Stories of encounters with snakes on hiking trails, or of the creatures slithering into people's homes on outlying islands, are commonly heard at parties.

Recent reports of a cobra entering a Sai Kung home, and a python killing a dog out on a walk, have gone viral. Snakes are routinely spotted in urban areas, too; one was sighted last month in Happy Valley.

Walking to her Causeway Bay flat with her mother, Denise Chan Lok-yan was so surprised to be bitten by a snake that she didn't believe it: "I looked at my foot, saw blood and thought, 'that stick was quite sharp', but then I saw the snake escaping. We got so nervous we called an ambulance. They took me to a hospital in Wan Chai, but they didn't have the antivenom so I started to get really nervous."

She had been bitten by a bamboo pit viper, the most common cause of snake bites in Hong Kong.

The viper's bite is rarely fatal but can cause extreme pain, bruising and swelling. Chan spent four days in hospital under observation before the swelling and pain subsided.

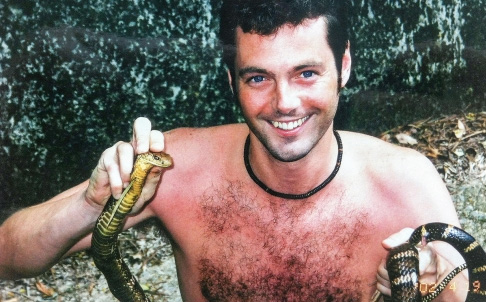

Stephen Loman and William Sargent know more than most just how closely we live with snakes. Although the pair balk at the term snake hunter, they have been rescuing, photographing and releasing snakes in the wild in Hong Kong for decades.

In that time, Loman, a finance professional, and Sargent, a race organiser, have caught and released more than 1,000 snakes and suffered hundreds of bites.

Even so, both argue - and experts agree - that the fear of snakes is often misplaced. "Snakes get a bad reputation," says Sargent. "A lot of people don't know much about snakes. That fear or ignorance leads to killing snakes for no real reason."

In his experience, it is humans who are a menace to snakes, not the other way around. According to the Hospital Authority there hasn't been any death attributed to a snake bite in more than 20 years although Hong Kong has some particularly venomous species such as the banded krait, Chinese cobra, coral snake and the red-necked keelback.

Dying from a snake bite, even from the most poisonous species, is "very rare" in Hong Kong for several reasons, Lau explains. The city is small, has good infrastructure, and a high standard of medical care. No matter where someone is bitten in Hong Kong, they are never more than an hour away from hospital, and all major hospitals carry antivenom.

It may come as a surprise that even species that are endangered elsewhere sometimes boast robust populations here.

"A few species that are found in Hong Kong are listed as at risk, but it doesn't mean the local snake population is at risk," says Dr Billy Hau Chi-hang, a principal lecturer in biological sciences at Hong Kong University.

Take the king cobra, for example. In the region, it is endangered because people eat it and hunters have decimated snake populations in southern China to supply restaurants. But while some Hongkongers dine on snakes, too, the supply is imported and such hunters are rare here.

Moreover, our country park system presents an extensive habitat where snakes can live relatively unmolested. Strict laws prohibit anyone from interfering with wildlife in the nature preserves and parks that cover about 40 per cent of the land surface.

That said, it's not all good news for snakes. Those inhabiting hilly terrain, where most country parks are located, fare better than those in lowlands, which are more developed. Highly specialised snakes have a much harder time.

One fascinating species is the burrowing Hong Kong blind snake, a species that was first spotted here in 2004, which surprised experts.

Another sighting quickly followed, but it has not been seen again in the intervening 10 years. Lau now believes the snake has been eradicated.

Sea snakes are another group struggling to survive. While there are six species of highly venomous sea snakes native to Hong Kong, there hasn't been a sighting since the 1970s. Lau attributes their disappearance to rapid degradation of the marine environment.

But if snakes killing humans is mostly unheard of, the same can't be said for humans killing snakes. Loman and Sargent have innumerable stories of finding snakes killed by people throwing rocks, or having their heads chopped off.

Loman cites an encounter in 2002 that he feels is typical of people's reaction to snakes here. He had been out hiking in a Lantau country park when he spotted a cobra trapped in a tunnel. As he tried to rescue the snake, a family walking on a trail about five metres above Loman saw what he was doing, and asked that he allow them to kill the creature in case it hurt the children.

At the other end of the spectrum are animal lovers like the woman who sought Sargent's help three years ago when she found a snake in her garden. She was afraid that if she called the police, they would kill it. "She had mentioned the snake was about six [1.8 metres] or eight feet long; I assumed from experience that it was more likely to be four or five feet long. When I got there, she pointed to it, and it was 13 feet long. It was the biggest snake I'd ever seen in Hong Kong."

It was returned to the wild, he says: "That was good fun. That was a strong, huge snake."

Asked if they've been scared, Sargent and Loman laugh. "There's a big misconception that snakes are aggressive. But they're not; they're defensive," Sargent says.

"So when a cobra hoods up or a rat snake opens its mouth or postures towards you … in its mind it's fighting for its life. So, if you keep still and give it a bit of space, it will 100 per cent of the time disappear and not harm you."

So if you spot a snake in the wild, don't panic and just leave it be. But if a snake enters your home, call the police, as they are trained to deal with them.

After being bitten, Huber called the police who quickly transferred her to Queen Mary Hospital. Prescribing antivenom can be tricky - and this is why it is often a good idea to try to take a picture of the snake that bit you - as different snakes need different antidotes.

But Huber and her boyfriend have pet snakes and an interest in reptiles, so she knew it was a cobra.

"You do get quite emotional at the time. Your mind races, and you wonder what is going to happen. I did worry if I was going to die or lose a limb."

Still, Huber never blamed the snake: "It was an accident; the poor thing was just trying to find its dinner and I stepped on it."

At the hospital, her fears were quelled: "The staff really know what they are doing. I was given a few doses of antivenom, and they released me the next day."

Huber emerged without lasting effects aside from a spot of nerve damage in her ankle. The snakes of Lamma were not so lucky, she says. "When I was bitten, the story spread like wildfire. Within a couple of weeks, two cobras and two bamboo pit vipers had been stoned to death. One of my friends witnessed a cobra having its head cut off with a brick."

The killings broke Huber's heart. "That cobra … has a right to be here. We are the ones cutting down the trees, destroying their habitat to build ours."

In response to the snake killings, Huber put up a post on her Facebook wall, pleading for people to treat snakes with respect. She ended with the comment: "While I would never recommend what I've been through, the whole experience has only made me respect snakes more. Be vigilant, yes, vigilantes, no."