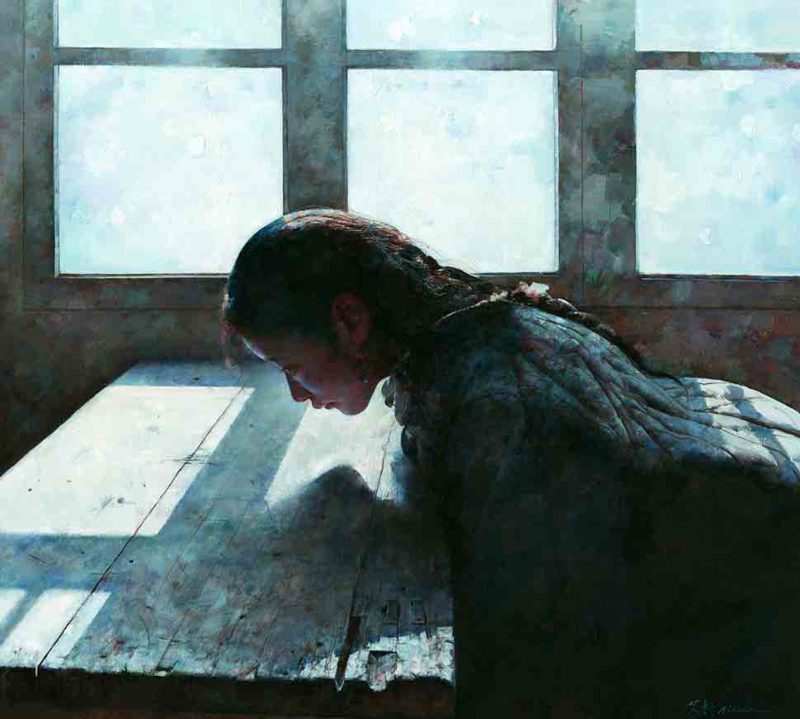

Ai Xuan is a realist and proud of it. Even as avant-garde Chinese artists attract ever greater attention – and rake in record prices – Ai has only become more fervent in his devotion to his “old-fashioned” style of painting.

Chatting under the gaze of his paintings of Tibetan peasants, he repeatedly exalts the realist approach – the difficulty of the medium, the skill required – and reacts with confusion towards anything modernist.

The more “real” the painting the better, says Ai, who was in Hong Kong two weeks ago to attend the Fine Art Asia show and the opening of his exhibition “Colours From Ink” at the Kwai Fung Hin gallery.

So it’s startling when he gestures to the bright-eyed Tibetan families staring out from the walls and says: “These are all my creations. None of them are real.”

This contradiction defines Ai Xuan: an artist whose life has been spent deconstructing reality and using the pieces to create fantasies that have proved popular with the mainland elite. The Sacred Mountain, one of his oils, fetched 20.7 million yuan (HK$26 million) at the Beijing Poly auction in 2010, while at a Sotheby’s sale in Hong Kong this year, another work, Longing, went for HK$9.6 million.

His latest Hong Kong exhibition represents a departure: after a lifetime spent working in oils, the show features 30 ink drawings – his first gallery show involving the medium.

As a teenager, Ai, the son of a famous political poet, studied realist painting at the Central Academy of Fine Arts at a time when art students in China had limited options.

“There were only two things you could learn: traditional ink painting, and realism,” he says. “All of the realism teachers were from Russia.”

Ai chose realism and has never looked back: “Realism is the only style I’ve ever known.”

After the Cultural Revolution waned in 1974, Ai joined the army and was sent to Sichuan, where he got his first glimpse of Tibet, just over its western border. It was the defining moment: even more than painting, he adored travel and fell in love with Tibet.

To this day, when he creates a piece of art, Ai first heads to Tibet.

He travels with no sketchbook and no camera – just an open mind – to soak in the feel of the place and the people. Then he returns to Beijing and, back in the comfort of his home and studio, ruminates on his trip, making sketches.

He creates a tableau in his mind that captures something of his experience – the essence of his feelings.

“It’s like a movie: I’ll put a person here, I’ll put these houses here. There is nothing real. I’m setting a scene.”

Then, the surprising part: before putting brush to canvas, he returns to Tibet. This time he travels not as a tourist, but as a collector. First he hunts for the right person. “I look for a model who fits my idea.” Then the right setting: “I find the houses that were in my imagination. I find the right background.”

For Ai, this is the most thrilling part of the process. “It makes me so happy. It makes me feel like a director.”

He brings these real people to places that match the backdrop in his imagination. Then he paints the scene.

His paradoxical methods give an inkling there is more going on beneath the surface of the images, something which is as troubled and contradictory as the man himself.

It’s impossible not to view the brazen process as a political act: a privileged scion of the Chinese art establishment using his access and power to literally mould a place and a people to fit his idealised notion.

He says as much himself: “I’m expressing my own ideas about the world through the gestures and actions of the Tibetan people.”

The results are often sentimental and, like the man, defiantly old- fashioned. Ai is very aware of the way his paintings are seen by a generation brought up on “modern art with its abstractions, video installations, photography and cartoons”.

There is a certain militancy to how he describes realists’ work, enshrined in the Beijing Realism School (now the China School of Realism) he founded in 2004, which quickly became one of the most influential groups in mainstream Chinese art.

“No matter what is going on outside, they’re not going to affect us. We’re tough as rock. This genre is tough as rock,” he says.

And, what does he think of all of that art that is “going on outside”? He dismisses it.

“I’ve seen it, but it is all too simple for me. I prefer more difficult art – art that requires more skill.”

Though he doesn’t mention him by name, there is no doubt Ai Xuan is referring to his stepbrother, Ai Weiwei, China’s most famous dissident artist who has made a name for himself by pushing the boundaries of both art and the tolerance of the Communist Party.

You can tell Ai Xuan is weary of questions about his brother. He tries to be diplomatic but doesn’t mince words: “I really cannot understand his art so it would be better if I did not comment on it ... When I look at his work, his techniques, I don’t see anything brilliant. It is not creative.”

If that seems harsh, Ai Xuan claims his stepbrother has said worse things about him in the press: “He’s said I am tong liu he wu,” he says, using a Chinese idiom which means being in collusion with wrongdoing.

Strong words, but hardly surprising. Theirs is a strange relationship: one brother a self-professed enemy of the status quo, the other, part of the status quo (apart from founding the school of realism, Ai Xuan is also the director of the Beijing Fine Art Academy).

Still, the longer you spend with Ai Xuan and his work, the more you realise that for all the false idealism and pouty peasant girls, there is, at the core, something darker.

In almost every scene there is a sense of hardship in the hardscrabble lives of the Tibetans, an unforgiving chill to the setting, a pervasive sense of suffering and isolation.

If his paintings really are of his own interior world – as he says they are – then Ai must be a troubled soul.

What is the source of this suffering? Without hesitation, he says his family.

If having a brother such as Ai Weiwei isn’t complicated enough, Ai Xuan is also the son of one of China’s most venerated poets, Ai Qing, who came to prominence under Mao’s regime.

Ai Xuan came of age during one of the most tumultuous times in Chinese history, and watched as his father was exalted, then vilified, then finally redeemed.

All the while Ai’s home life was spinning out of control. His parents divorced and a stepmother moved in, then his father was denounced as a rightist and sent to the countryside for rehabilitation. In the suspicious, dangerous climate of the times, the whole family was isolated.

“I was quite lonely as a child,” Ai says, then continues in a torrent of memories. “I was abandoned by my family and spent most of my youth ... on my own. My parents fought with each other all the time. When my father was accused, the bad feelings lingered for more than 20 years.”

He pauses for breath and looks down at a brochure of his paintings on the table. “So of course, what I paint is how I felt throughout those years.”

The more you learn about him, the easier it is to see Ai Xuan in his paintings: the cold desolation of the lonesome Tibetan plateau, the grinding daily struggle of the solitary figures.

But even that is missing the point. For the truth, Ai says, look at the eyes: “Eyes are a person’s identity ... If you paint them just a little bit differently you give an entirely different impression to people.”

His subjects’ eyes are ablaze with the determination to carry on, to defend what defines them against the inevitable march of time.

It is all there in his paintings: a series of troubled self-portraits constructed from the lives of other people very far away.